The Craftsmanship Revolution: Nothing is Crafted Like a Lexus

Lexus uses the latest technology to design and build its cars, but people remain at the heart of everything we do.

True to our proud status as a human-focused company, Lexus relies on the skills of its takumi craftspeople to achieve the finest quality and luxury standards. These dedicated artisans have talents beyond compare, and they lead and train the men and women who bring a very special quality to every Lexus that’s built.

Traditions in a high-tech world

Inside a Lexus factory you’ll find some of the world’s most advanced technology at work. But every bit as important as the robots and lasers are skills and techniques that date back centuries and which could never be replicated by a machine.

When it comes to achieving perfect quality and a flawless finish, it’s the judgement of the human hand, eye and ear that count. These are the talents of the takumi, craftspeople who have dedicated their lives to developing particular skills, and whose work is the defining factor in Lexus’s hand-crafted luxury.

Who are the takumi?

The takumi has a great heritage in Japanese history as a master craftsperson. Even today, achieving takumi status take years of dedication and training, with meticulous attention to detail and a commitment to excellence.

At Lexus, each takumi has a minimum of 30 years’ experience, giving them an unmatched depth of knowledge in their field. To bear the name is the highest honour among the ranks of engineers and it’s a privilege held by only a few: of the 7,700 workers at Lexus’s Miyata factory, just 19 are takumi.

Training people, training robots

Every takumi has a responsibility to pass on their skills to the next generation, ensuring that essential talents are maintained. But just as much as they teach their human colleagues, they also contribute to designing better robots.

The takumi provide vital insights when it comes to designing automated processes, to help gain the best results. For example, the motion of an automated paint-spraying arm matches the sweeping arm movement of a human master craftsperson.

Touch-sensitive

The Lexus takumi have a legendary sense of touch and they use this sensitivity to detect the slightest imperfections, down to fractions of a millimetre – a level of accuracy a machine cannot match. More than that, a machine can only find flaws it is programmed to detect, making the sharp eyes and fine fingers of the takumi even more crucial.

Motomachi masters

Motomachi is the home of Lexus’s LC flagship coupe, where eight takumi lead quality teams that check every step in the car’s production. For example, when the bodywork has been stamped and welded together, a master craftsperson checks everything is perfectly aligned by sight and touch. There are more than 800 individual checks to be made, combining human sense with electronic tools.

At the other end of the production line, the finished car moves into a futuristic light-filled glass booth to undergo a detailed inspection by two of the factory’s most skilled craftspeople, covering 700 different check points. They scrutinise details that even customers might never notice, such as the precision finish of surfaces inside and out, the evenness of colour and the operation of every working part.

All this takes place in complete silence: acute hearing is another takumi skill, so that any abnormal sounds can be picked up and their source traced.

Takumi at the wheel

The final stage before a Lexus leaves the factory and heads for its new owner is a test drive on a purpose-built track. Once again, it’s down to a craftsperson to ensure performance is exactly as it should be. Lexus relies on the master’s sensitive touch to assess feedback through the steering wheel and ensure all parts are working properly.

Painstaking design

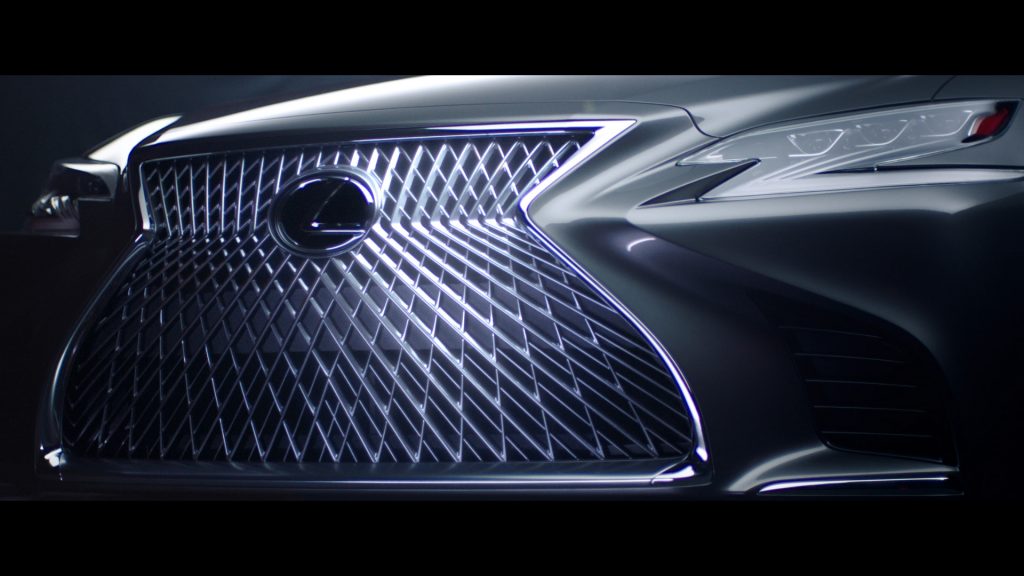

The spindle grille has quickly become a key feature of every new Lexus design. Each one comes with a distinctive mesh pattern that adds to the car’s character and visual impact. Of course, computer-aided design plays its part in creating a sophisticated network of lines and shapes, but the precision touches are the work of the Lexus takumi.

Take the grille on the LS 500h flagship saloon as an example. Computer modelling set out the mesh pattern with reasonable accuracy, but a skilled modeller then individually adjusted the curved surface of 5,000 separate motifs to achieve precisely the right effect. The task took six months to complete.

Hand-made tools

Every takumi needs the right tools for the job, and will even craft them themselves if necessary. That’s the case with Yasuhiro Nakashima, who spent 27 years learning and honing his craft – filing, shaping and polishing the metal moulds used to make the LS’s spindle grille.

He has made his own, customised set of tools, including hand-made bamboo instruments to shape the finer details. The machines and processes used to make the mould are among the best available, but the perfect finish still requires a remarkable human skill. Nakashima refines surface smoothness to within a tenth of a millimetre – picking out imperfections even the best robotic milling technology cannot detect – and hand-polishes minute surfaces in specific directions to achieve the best reflective qualities.

So crucial are his skills to the process, he actually worked with the LS’s design team to ensure the best outcome.

Sword-making skills

The ES F Sport saloon has a very special interior trim, called Hadori. It’s a modern interpretation of a very old and revered Japanese technique for polishing the blades of a katana sword.

Toshihide Maseki, designer of the ES’s cabin, sought out artisans working today who practise sword-making traditions that go back more than seven centuries. They produced a prototype by hand which could then be replicated using a machine. Although the equipment was fed precise data related to the details of the Hadori pattern, the results did not match the look of the prototype.

Maseki explained: “Studying the pattern with a microscope, I discovered randomly created lines that could not be replicated with a machine. But these lines gave the overall design its powerful impact.”

These “random lines” had been instinctively added by the craftsmen, bringing to bear their many years of experience and keen understanding of katana aesthetics. “Although being refined is an important quality in craftsmanship, a product is incomplete without the addition of more human, more instinctive elements that are not based on simple calculation,” said Maseki. “Being machine-made but artisanal, being refined but having impact – these may seem like contrasting elements, but through a lot of trial and error, we were finally able to achieve this combination, in the process imbuing the door trim of the new ES with a deep katana-like beauty.”

Flawless stitchwork

The beautiful stitched seams of the leather upholstery inside a new Lexus may look simple and elegant, but they take tremendous skill to achieve. For a flawless finish, every stitch has to be precise, every time.

Led by a takumi, a dedicated and highly skilled team are responsible for the stitchwork, selected for their dexterity and attention to detail. Very few make the grade: there are just 12 in the team at Lexus’s Miyata factory.

Every one of them has had to train at a stitching dojo – like a formal martial arts class – for three months, under the takumi’s direction. Ten different techniques have to be mastered before they can progress to production work.

Hand-crafted woodwork

A wooden steering wheel is one of the traditional hallmarks of a luxury vehicle, but where Lexus’s shimamoku wood is concerned, the production is unique.

Shimamoku has a distinctive pattern of ebony and grey graining that’s similar to exotic and rare timbers such as zebrano. In fact, it is derived from sustainable sources and created using master craftsman skills. It’s a combination of natural material and man-made techniques that creates an object that is both simple and complex – a quality the Japanese call shibumi.

Sheets of wood less than 1mm thick are shaved from hardwood logs, then stained and treated to achieve a mottled effect. The sheets are stacked in alternating bands of contrasting colours, bonded with glue and clamped. Once set fast, the wood is sliced lengthways to create new layers with the special Shimamoku pattern.

It’s a job that involves three different suppliers and 67 separate processes, and takes 38 days to complete, with much skilled hand-work in bonding the veneers onto a solid wood form, sealing and polishing.

ENDS